Africa, the world’s second-largest and second-most populous continent, despite being one of the continents which embraces democratic form of governance, faces a series of leadership challenges, including that of sit-tight leadership where the Heads of State desire to overstay their positions beyond the constitutionally stipulated terms.

The laws of many African Nations like Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, Niger, Mali, South Africa, Namibia, Benin among other, stipulate a two-term limit of four or five years per term. However, for many decades, several African leaders have manipulated the constitution and the institutions in their respective countries, to suit their desires to perpetually remain in power.

For nearly four decades, President Yoweri Museveni has stood at the centre of Uganda’s political life, growing from a rebel leader who promised democratic renewal, into one of Africa’s longest-serving presidents. His story is not just about one man or one Country; it reflects a broader central pattern in which liberation heroes and activist leaders gradually transform power into permanence.

Museveni’s tenure since 1986 calls for a deeper check into Africa’s continuing struggle with sit-tight leadership where constitution amendments, questionable elections, and corruption of security agencies have replaced the original ideals of change, and where the question of succession remains Africa’s most sensitive political burden.

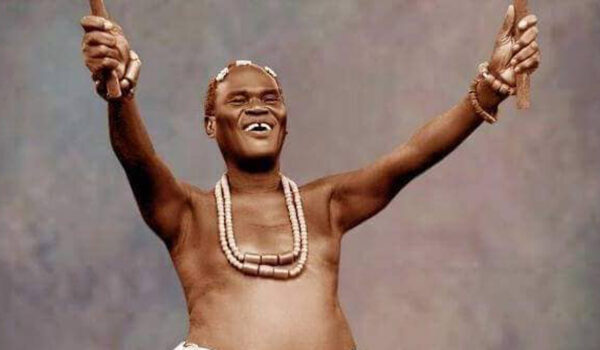

The Ugandan-born Yoweri Museveni, at his swearing-in ceremony, initially kicked against leaders who overstay while in office, promising a return to democracy. He famously stated that the problem of Africa in general and Uganda in particular is not the people but leaders who want to overstay in power.

Museveni, said that democracy was the right of the people of Africa and that the government must not be the masters but the servers of the population. He suggested that democracy would be built from the ground up, with village committees that would serve as the watchdogs for society against misuse of authority.

Museveni’s early years in power were widely praised. He stabilised a fractured country, restored basic security, implemented economic reforms backed by international institutions, and positioned Uganda as a regional powerbroker. In the 1990s, donors lauded Uganda as a model of post-conflict recovery, and Museveni enjoyed significant diplomatic goodwill.

However, embedded within his governance model was a contradiction that later explained his legacy. Uganda’s no-party system, justified as a way to avoid rigid politics, effectively concentrated power in the presidency. While elections were held, political competition remained tightly managed. Over time, the language of stability replaced the language of transition.

Critics and analysts have observed that the promises made by Museveni have not been fulfilled. Over the decades, his administration has passed several constitutional amendments, both the presidential term limits and the presidential age limit, which have allowed him to run for office continually.

Beyond Museveni, the story of sit-tight leadership in Africa is ultimately a story of unfinished democracy. It reflects weak institutions, individual ambition-driven politics, external involvement, and societies still negotiating with accountability.

Museveni’s line is not unique. Africa’s post-independence history is filled with leaders who arrived on waves of popular support, only to establish themselves over time. From Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe to Paul Biya in Cameroon, Denis Sassou Nguesso in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Teodoro Obiang in Equatorial Guinea, and Gnassingbé Eyadéma (and later his son) in Togo, the sit-tight phenomenon has cut across region, and generation.

In DRC, Nguesso was in power for 36 years; Gnassingbé Eyadéma served as the third president of Togo from 1967 until his death in 2005, ruling for 38 Years, after which he was immediately succeeded by his son, Faure Gnassingbé who ruled for 20 Years; Equatorial Guinea’s Obiang has been in power for 41 years; Rwanda’s Paul Kagame for 20 years; Paul Biya of Cameroon for 38 years; Chad’s Idriss Deby for 30 years; Isaias Afwerki has also been in power for 27 years in Eritrea; and Ismail Guelleh for 21 years in Djibouti.

In countries like Nigeria, political leaders have deployed same tactics of institutional compromise and manipulated elections to win second term elections. While no past Leader of the country has succeeded in becoming a sit-tight leader in the shape of Uganda’s Museveni, the same pattern of unpopular leadership forced on the people through non-democratic means, is evident.

Read Also: Ugandan President, Museveni, Seeks 7th Term after Four Decades in Office

Yoweri Museveni’s long grip on power mirrors a wider African problem in which constitutional provisions are repeatedly bent to suit individual ambition, while democratic ideals are invoked more in speech than in practice. His journey from being a reformist rebel to a fixed ruler emphasizes how liberation credits and early governance successes often become shields against accountability.

Across the continent, the persistence of sit-tight leadership continues to test the strength of institutions, the credibility of elections, and the resilience of civic space. Until African democracies move beyond personalities and invest decisively in independent institutions, transparent succession, and respect for term limits, the cycle of prolonged rule will remain a recurring burden, one that delays political renewal and undermines public trust in governance.

Comments